This is the second of three posts

presenting and developing my recent slide talk

Contemporary Art as Buddhist Practice.

Here, I'll discuss a single work - a series really - by a painter

well known from the 1930s into the 1960s.

I'm going to ask you to use your imagination,

which is more effective in a live setting since I can withhold the image.

˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜

I’ve

been showing some slides from early Buddhist painting,

done by monks and artists familiar with the Buddha Way,

And

a few Paintings by Modern artists who shared that motivation.

I will now introduce to you one

Midcentury work in particular.

Though

many other modern paintings would be worth the trouble, this is something wonderful.

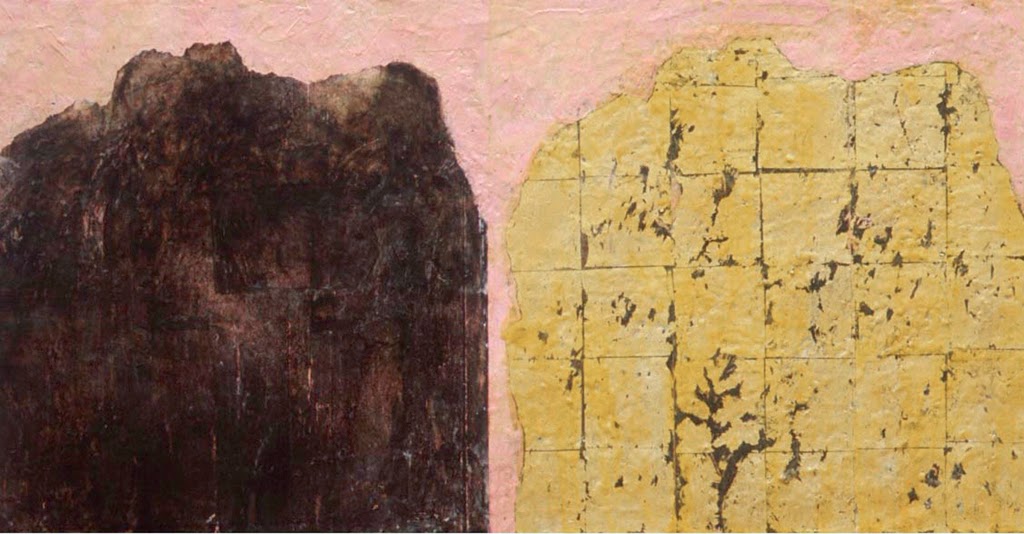

Close your eyes and imagine please, a square canvas.

It’s almost as wide as your outstretched

arms, higher than your head, down to about your knees.

The

canvas is all black. The painter

was well acquainted with the Buddhadharma.

He

wrote out 12 rules:

No

texture

No

brushwork or calligraphy

No

sketching or drawing

No

forms

No

design

No

colors

No

light

No

space

No

time

No

size or scale

No

movement

No

object, no subject, no matter. No symbols, images or signs. Neither pleasure

nor paint.

As

you gaze into this black field, devoid

of mark or space or time, you begin

to distinguish some “resonance” in the blackness.

It’s

not just black. Maybe there is a

design, a division, though you’re not quite sure you saw it.

Now

open your eyes.

10

minutes in front of one of Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings can change your life.

He

painted them, by hand and brush, for the last many years

of his life.

Always

the same, always new, he referred to them as

The

Last Painting.

Reinhardt wrote in 1962:

“The standard of art is oneness and fineness, rightness and purity, abstractness and evanescence.

The one thing to say about art is its

breathlessness, spacelessness and

timelessness.

This is always the end in art.”

For

a moment, imagine yourself making a painting like this.

What

would shift in yourself as

you mix these colors so

black, yet not black,

and

apply them according to his 12 rules, stated as they are, in the negative?

What

would you have to relinquish?

˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜˜

Now, I said above that ten minutes in front of one of Ad Reinhardt's paintings

could change your life.

I don't know if that can happen in front of a computer screen. I have written elsewhere about the confusion about art that comes in a time like ours when all information, standing in for experience, takes place in reproduction. This has been a topic since the 40s at least, but now with electronic communications so ubiquitous, we tend to forget that works of art are there to be contemplated

in person, in real life.

The next time you are in a museum that has an Ad Reinhardt Black Painting

do not miss the opportunity to spend 10 - 60 minutes in quiet contemplation.

People pass them by. Lao Tsu said the Tao that is not laughed at is not the true Tao.

Bibliography

Baas,

Jacqueline. 2005. Smile of the Buddha:

Eastern Philosophy and Western Art

from Monet to Today. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California

Press.

Baas,

Jacqueline and Mary Jane Jacob. 2004. Buddha

Mind in Contemporary Art.

Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

Rose,

Barbara Stella. 1975. Art as Art: The

Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt.

Berkeley,

Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

The second book on this list was not a specific reference for this post, but is here included because of its important relation to the first book by the same author. Jacqueline Baas and Mary Jane Jacob "co-organized...a program...entitled Awake: Art, Buddhism, and the Dimensions of Consciousness. From April 2001 to February 2003 this consortium effort brought together arts professionals, artists, and others to investigate the relationship between the meditative, creative, and perceiving mind; and the implications of Buddhist perspectives for artistic and museum practices in the United States. It led to more than fifty exhibitions, performances, and public programs from 2002 to 2004." (from the publisher's page)

It's a fascinating and inspiring book. It offers a new take on Marcel Duchamp and describes the ongoing work of contemporary artists working today. There are no painters mentioned.

In The Smile of the Buddha, Ms. Baas has essays on Monet, van Gogh, Gauguin, Redon, Kandinsky, Brancusi, Duchamp, O'Keefe, Noguchi, Reinhardt, Yves Klein, Jasper Johns, John Cage, Nam June Paik, Yoko Ono, Laurie Anderson, Agnes Martin, Robert Irwin, Vija Celmins, and Richard Tuttle.

Barbara Rose edited Reinhardt's enigmatic and slyly profound writings.